The FinTech Divide: Why is credit no longer reaching where it’s due?

Swiggy just launched Crew, an invite-only concierge app for affluent customers who need help planning European vacations and securing international driving licenses. The food delivery giant that once democratized restaurant access is now chasing premium customers who can afford INR 50,000 memberships for lifestyle management.

This isn't just Swiggy. Across India's fintech landscape, companies are discovering that serving fewer, wealthier customers is simply better business than solving inclusion challenges.

The lending data from the recent CMI report reveals the shift. New-to-Credit consumers, those getting their first formal credit, have dropped from 21% of loan originations in March 2023 to just 16% in March 2025. These are exactly the people fintech promised to serve. Meanwhile, the Above Prime segment has grown from 17% to 21% of originations over the same period.

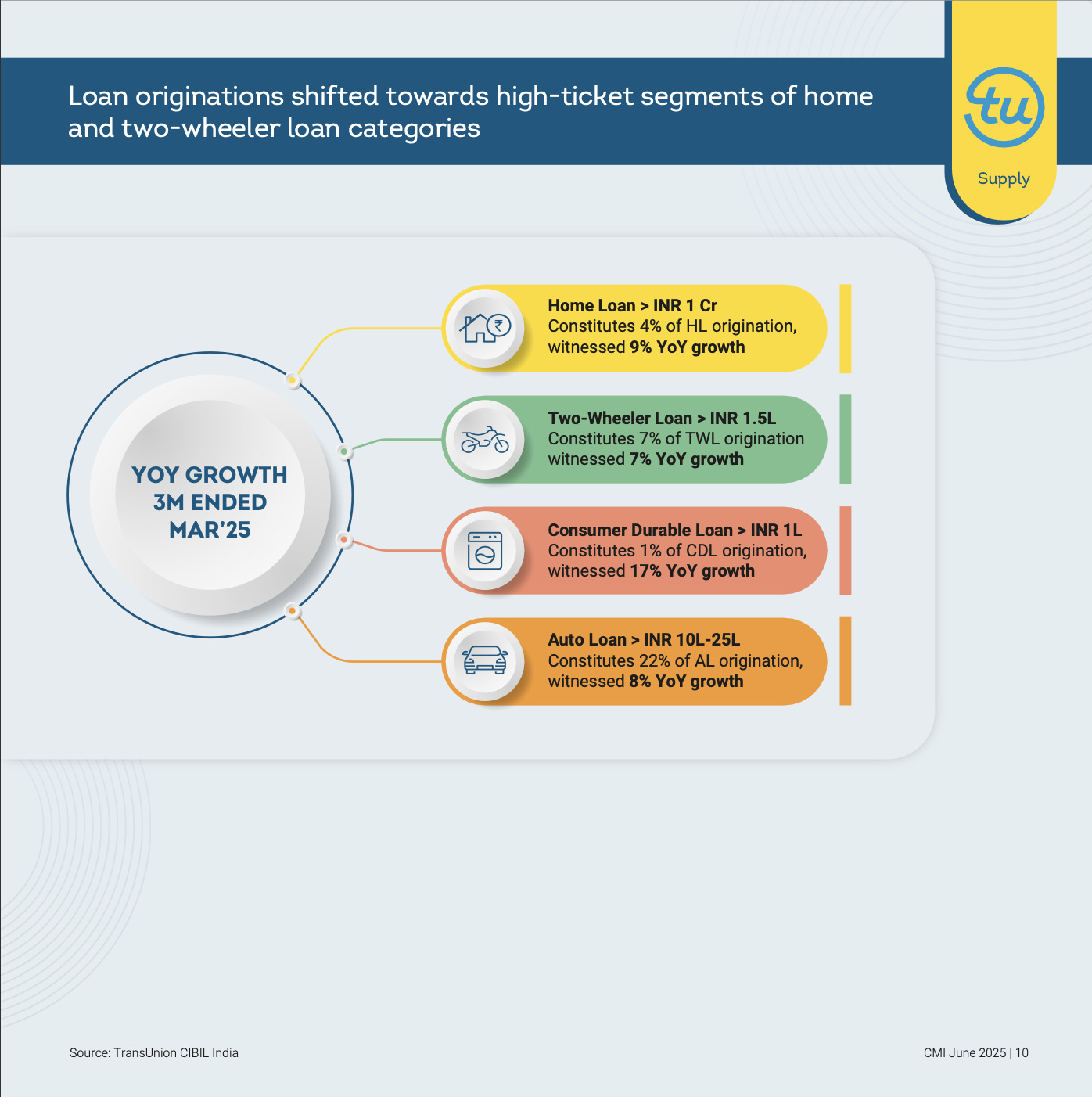

The real story lies in ticket sizes. Home loans above INR 1 crore, representing just 4% of home loan originations, are growing at 9% annually. Two-wheeler loans above INR 1.5 lakh constitute 7% of two-wheeler originations but surge 7% year-over-year. Consumer durable loans above INR 1 lakh represent only 1% of consumer durable originations, yet jump 17% annually.

The business logic is straightforward. Wealthy customers have documentation, credit histories, and collateral. They understand financial products and rarely need hand-holding.

Compare that to serving the underbanked. These customers need vernacular interfaces, alternative credit scoring, extensive customer support, and physical touchpoints in smaller towns. The operational complexity translates directly to higher costs.

The technology that was supposed to level this playing field has actually tilted it further. Digital KYC and automated underwriting work best with customers who already have digital footprints. The more sophisticated fintech becomes, the better it serves people who are already well-served. This makes strategic sense if the alternative is competing in crowded, low-margin segments with complex operational challenges.

The convergence is striking. As fintech matures, companies face pressure to improve unit economics. Individual rational decisions by countless companies are producing a collectively irrational outcome: the most innovative financial sector in the world is optimising for people who need innovation least.

Perhaps most troubling is how this dynamic affects innovation allocation. Engineering talent and product development resources flow toward problems that affluent customers face rather than barriers that prevent financial inclusion. AI-powered concierge services receive more development attention than alternative credit scoring for the unbanked. User experience optimisation focuses on premium features rather than accessibility for first-time users.

The result is a financial system that becomes simultaneously more sophisticated and more exclusive. Technology advancement and market concentration happen in parallel, not in opposition. The same digital infrastructure that could expand access is being optimised for customers who already have abundant financial service options.

This misallocation has compounding effects. As companies invest more heavily in premium services, they develop deeper expertise and stronger market positions in affluent segments. The competitive advantages created through serving wealthy customers make it even more difficult to justify investments in inclusion-focused products.

The convergence of these forces creates a feedback loop that strengthens over time. Success in premium segments generates resources that fund further premium innovation. Meanwhile, the infrastructure and expertise needed to serve underbanked populations remain underdeveloped.

The broader economic implications are concerning. Financial inclusion was meant to drive economic growth by bringing millions of people into the formal economy. When companies abandon this mission in favour of premium optimisation, they're failing to fulfil the social and economic potential that justified the regulatory support and public infrastructure investments that enabled their growth, don’t they?

But that wasn't always the plan. The digital infrastructure and venture capital that fueled India's fintech boom were premised on expanding financial access. Instead, we are creating conditions where serving the excluded is systematically more difficult than serving the included.

The path forward requires acknowledging that inclusion and profitability aren't mutually exclusive. They're engineering problems waiting for better solutions. Alternative data platforms are already proving that utility bills and transaction patterns can predict creditworthiness far more effectively than traditional scores. Vernacular interfaces aren't cost centres but moats that create defensible positions in underserved markets.

The companies building these solutions today aren't just serving the excluded. They're creating infrastructure for India's next growth phase. The potential market expansion from bringing the unbanked into formal financial services dwarfs any premium segment optimisation.

The choice facing fintech founders isn't between profitability and purpose. It's between short-term optimisation and long-term market creation. Building for inclusion isn't charity. It's the untapped frontier where the hardest problems hide the biggest returns.

This is all from me this week. I will see you next week.

Cheers,

Rajat