The blue pill vs red pill moment in India’s credit cycle

Credit is like a sphinx - it speaks in riddles. On good days it can be a barometer of the state of the economy and on others, it can hide ominous destruction of lives and livelihood within its complexities

I’ll leave it to the philosopher economists to grapple with its slippery nature. This week, I’m interested in making sense of a very specific aspect of credit – what does an increased credit offtake really mean in the face of an economic downturn?

Let’s dig into the most recent data and make sense of what’s happening.

Over the last year, non-food bank credit grew 12.6% compared to 4.9% a year agoas of May 2022. This massive increase indicates that economic growth, which had taken a hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, is now showing signs of recovery. In fact, borrowing continues to rise despite the fact that the central bank has raised interest rates to counter inflation. (India has had a chronic transmission problem,and that’s best delved into in a separate piece.)

Evidently, there is optimism in the air as individuals and businesses are projected to spend and invest more. However, while the numbers inspire confidence, a deeper inspection shows that the situation is more complex.

There are three major reasons why we must halt firing the celebratory fireworks for now –

Although credit has grown, deposit growth has failed to keep pace. The credit-deposit growth gap stands at a three-year high of 5%. Deposits, on which credit disbursed by banks is leveraged, will constrain the growth of loans if they do not grow alongside credit.

A closer look at the sectoral deployment of the total bank credit shows that loans used for consumption purposes rose exponentially.

For instance, consumer durables credit rose from 14.7% to 72.4% year-on-year, advances against fixed deposits went up from 2.6% to 17% and credit card outstanding from 14.3% to 30.1%.

Yes, overall credit has risen, but a large chunk of it comprises unproductive consumption loans that have a limited impact on long-term economic growth.

Loans to the industry have also increased. Credit to this sector had been plateauing at 29 lakh crores for two years, however, it has picked up in 2022 with Rs 31 lakh crores deployed to the sector.

Let’s examine point c. more closely.

There’s more to unproductive debt than consumption loans

When lenders are extremely risk averse and face uncertain economic conditions, the focus shifts from the larger economic good to short-sighted self-interest. These banks are more likely to disburse loans based solely on the value of collateral borrowers can spare, instead of comprehensive assessments of their ability to repay. This implies that banks have chosen to hedge their risk of a loss in the security of a collateral rather than go out on a limb and actually judge if the borrower has the intent and the ability to repay.

The downside?

Collateral isn’t as secure as it seems. Secured lending can actually be sometimes a misnomer.

Most collateral is subject to deteriorating market conditions. But more importantly, by centering their business models around collateral, lenders neglect to account for the viability of businesses and projects they lend to. In the long term, these poorly underwritten businesses may fail to generate profits, and ultimately to repay their loans.

(Sidebar: Read our guide on dynamic risk pricing and the role of machine learning in saving on credit losses.)

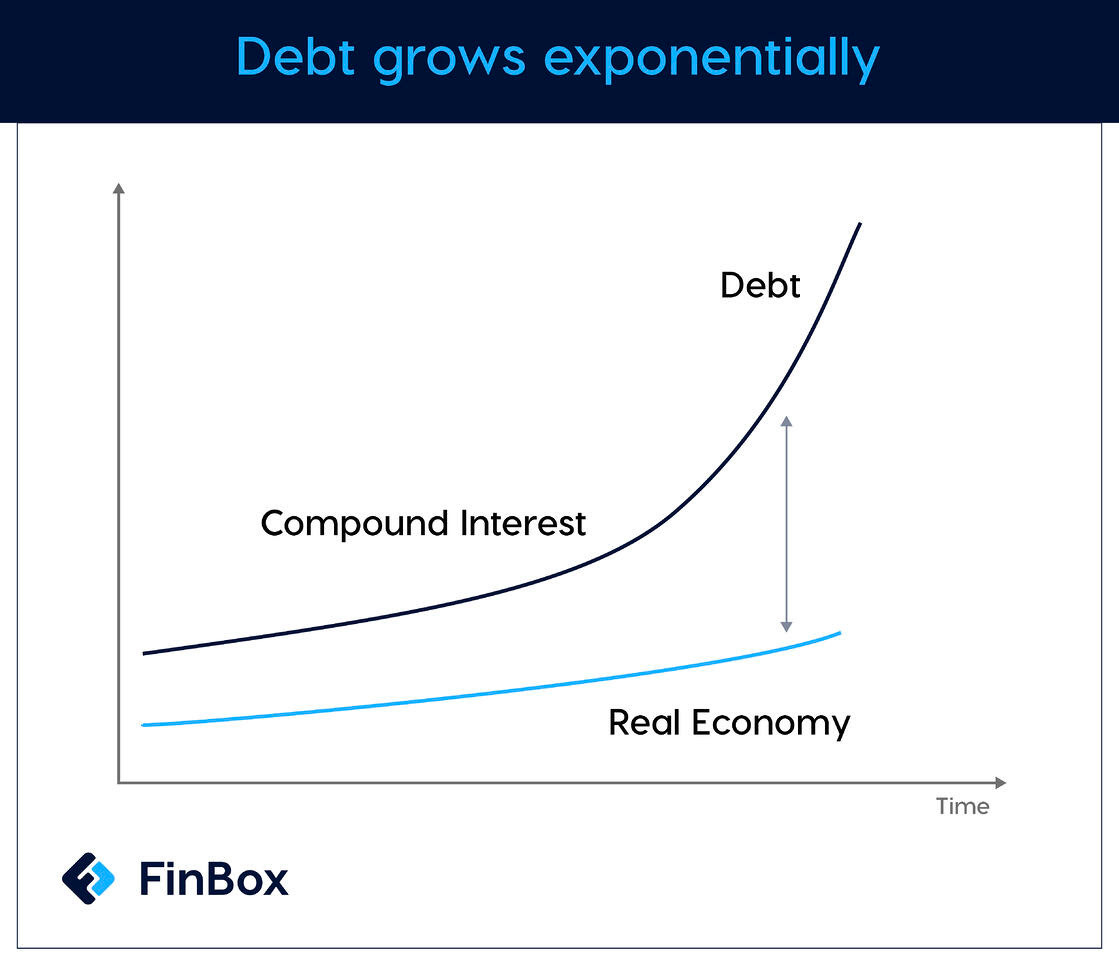

This attitude towards lending fosters unrealistic expectations of low risk and high rewards. In truth, what happens is that lenders are left pumping more credit into the economy to allow borrowers to pay the interest on their existing loans, resulting in a vicious cycle. On the flip side, the economy needs more fruitful investments to offset the effects of compounding interest if economic growth is to be achieved.

(Source: https://bit.ly/3InQSjm)

Lenders are left directing their funding towards retrieving their assets rather than investing back in the real economy. If prolonged, this leads to the creation of financial crises and bubbles.

For instance, corporations became highly leveraged post the 2008 financial crisis as debt continued to grow. In 2017, the proportion of debt to GDP hurtled towards unpayable numbers – 266% by some estimates. The overreliance on debt can have catastrophic effects as it depletes the equity of these companies in the real economy.

Redefining ‘productive debt’

There are loans that have long masqueraded as productive debt without actually contributing to overall economic growth. The rising instance of zombie firms in India is an interesting example. As I wrote in a previous edition of this newsletter, these companies are on the verge of closure and seek loans to ensure their survival. Banks who prop them up divert their funds to unproductive use and yield no results. (You can read the full piece here).

This is why there is a need to redefine ‘productive debt’ and go beyond the consumption-investment binary. In the interest of holistic economic growth, lenders are burdened with the responsibility to dig a little deeper before greenlighting large-ticket business loans.

Risk assessment for such companies or projects can start with a simple cost-benefit analysis. As a rule of thumb, the net present value ( present value of cash inflows - present value of cash outflows) should be greater than zero after the opportunity cost of the capital is accounted for.

The final decision on sanctioning these loans should only be taken after these calculations yield satisfactory results. Moreover, lenders should gauge whether the investment will be able to service the debt undertaken for the business. Lenders can assess business viability along these lines by thoroughly scanning risk profiles.

Economic downturns are uncertain and hardly the moments where one would stop to consider the very philosophical but highly relevant puzzle of productive vs unproductive credit. However, not spending the time and energy to ask tough questions such as this is likely to keep us vulnerable to more downturns.

I will leave you with a personal favourite Murakami quote.

“When you come out of the storm, you won’t be the same person who walked in. That’s what this storm’s all about.”

― Haruki Murakami, Kafka on the Shore

See you next week.

Cheers,

Rajat