Meet the zombies of India Inc.

Ah, the ’90s.

Culturally, those 10 years are a gift that keeps on giving. Whether it’s hip-hop, Harry Potter, Seinfeld, or Y2K — more than 20 years later, we still live for the nostalgia.

But not everything that came out of the ’90s is remembered fondly. Especially the vestiges of its economic conditions. The early years saw a global recession that tipped political scales across the world. Japan, in particular, was hit by a period of crippling stagnation famously dubbed the ‘Lost Decade’.

This spawned an army of what’s come to be known as 'zombie companies'.

Zombie companies are firms that, were it not for external financing, should have gone under. In the 1990s’ Japan, these were typically large firms that were deemed 'too big to fail', prompting bailouts from banks despite being unprofitable.

Fortunately, the island nation managed to bury its living dead during a favorable macroeconomic environment in the early 2000s through restructuring, downsizing, and selling unutilized fixed assets.

This is not to say that the credit-crazed fiends haven’t tried to claw their way back out. In the US, their threat became imminent once again following the 2008 global financial crisis. And in India today, their numbers continue to rise.

Anatomy of the Indian zombie

Research from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) shows that zombie firms are not very different from non-zombie ones in terms of size or age. But when it comes to profits, zombies deliver negative returns. The report recognizes a methodology where firms that are 60 to 90 days past due and have a credit rating below AA qualify as zombies.

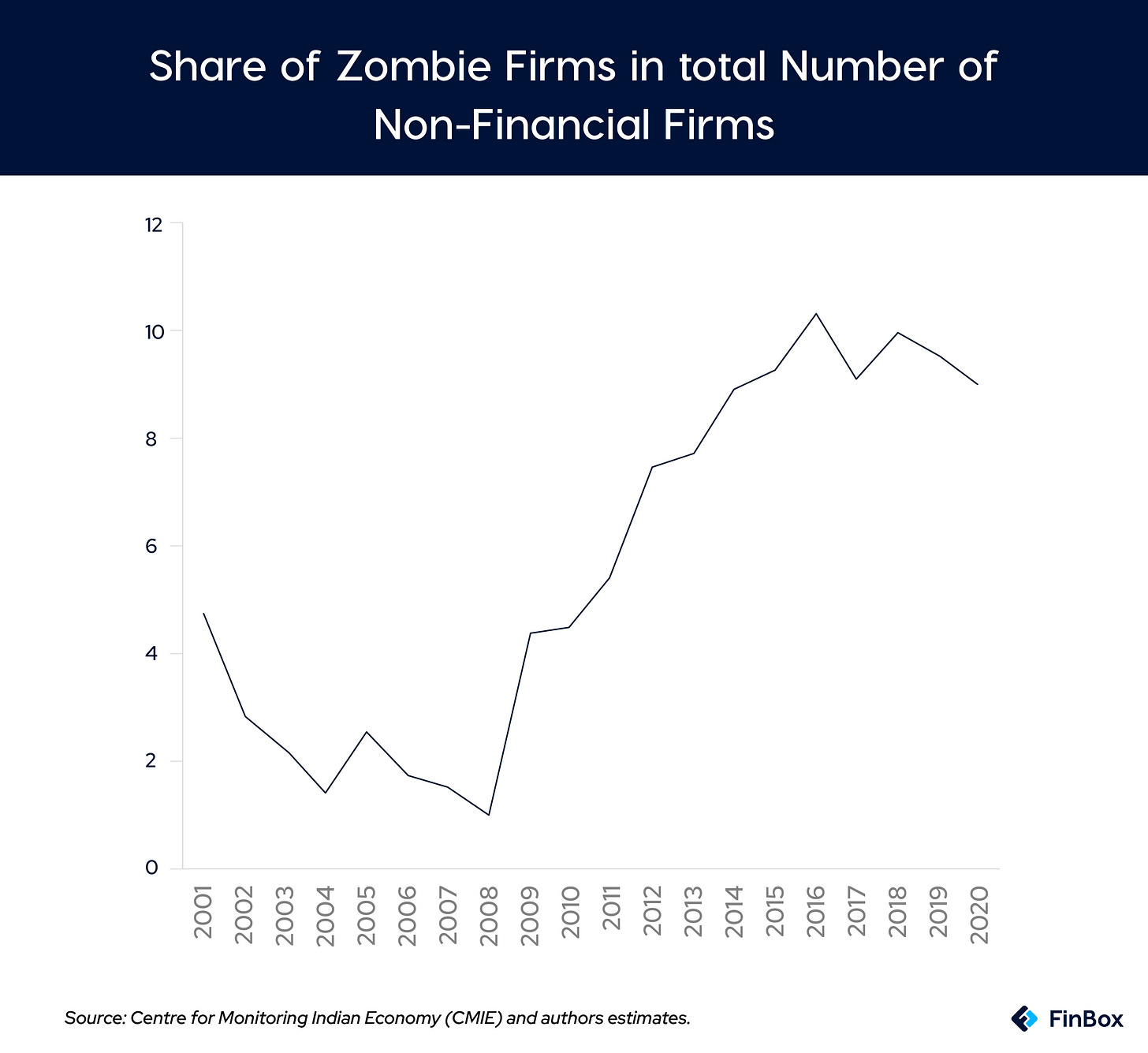

On average, zombies’ debt levels are 65% of their total assets, while non-zombie companies’ debt obligations stand at 35%. Zombie firms also tend to have relationships with fewer banks, although they’re longer. As much as 10% of the non-financial firms in the country meet the criteria of a zombie – the share steadily increasing in the post-financial crisis era.

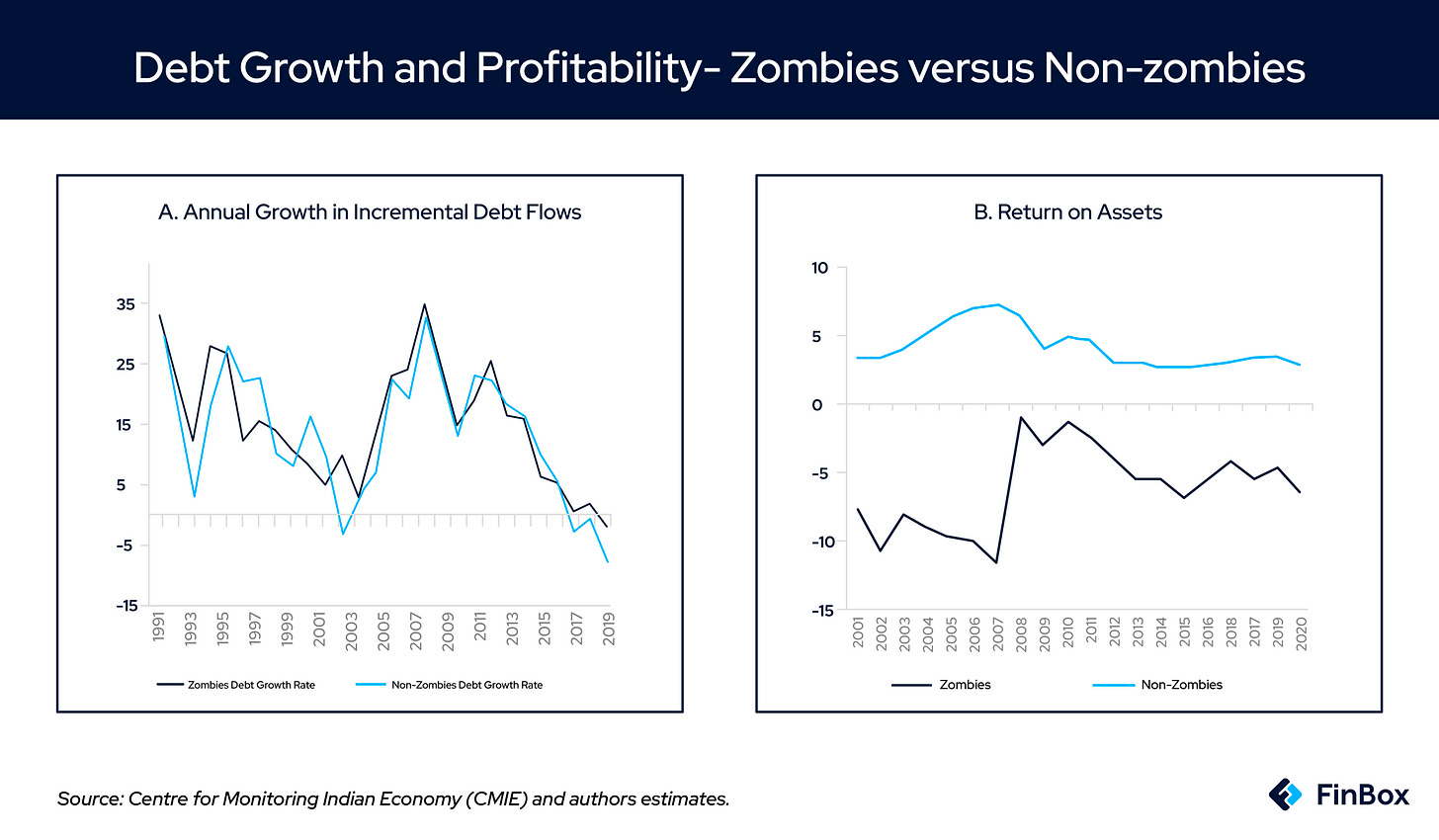

It’s also worth noting that zombies are more highly leveraged compared to non-zombies. Despite this, the cost of funds paid by zombies doesn’t differ vastly from what non-zombies pay.

Even though they are saddled with more debt than their equity, the graph above shows that the total share of these companies has been declining since 2016.

Sounds like good news? It may be grimmer than you’d think.

Companies on the verge of closure may seek loans that ensure their survival. These can prop them up as successful and help avoid bankruptcy. This could explain the plateauing of the curve post 2016. But since the funds aren't diverted towards productive use, they yield no results. This leads to gross misallocation of limited resources.

The research also showed that even though year-on-year growth for both zombies and non-zombies was very similar (thanks to ill-advised lending), their profitability paled in comparison each year.

It takes two to tango

Zombie companies don’t exist in isolation. They are propped up by banks that, like their debtors, are in trouble. These lenders are often at the risk of dropping below the minimum regulatory capital requirement and would readily lend to risky customers to resuscitate themselves.

Financing zombies is more prevalent in weaker banking systems. In competitive banking systems, the treatment of such firms differs from that of healthy companies. Banks are more inclined to lend to companies with stronger risk-reward profiles and better outlooks. In such a regime, banks do not care for their past relationships with a firm, effectively ruling out lending to zombies.

These companies rely more on funds taken from banks instead of market sources that better differentiate between good and non-performing firms.

Throwing good money after bad

Remember when I said that zombie firms tend to have longer relationships with banks? That’s because they perpetuate evergreening by taking out new loans from the same banks to service their debts. In fact, now there’s evidence to suggest that zombie firms also draw funds via related entities to avoid being detected.

This phenomenon may be even more detrimental, since it goes unnoticed on regulators’ radars. Unlike instances of direct evergreening that can introduce changes to the stock prices of these banks, indirect evergreening easily evades the markets’ attention.

For banks, evergreening helps hide their non-performing assets (NPAs). They continue lending to bad borrowers, allowing them to pay off their prior loans – at least the interest amount, if not the principal. In recent memory, IndusInd Bank and IL&FS have been accused of the practice.

The kingdom of the undead

Easing of monetary policy, warranted during difficult times like the COVID-19 pandemic, spurs the proliferation of zombies by unleashing cheap credit. It enables zombies to crowd out resources and take away opportunities from productive companies, ultimately hampering the growth of the economy.

The prevalence of zombie firms is also higher in weak insolvency regimes. But since the introduction of the Indian Bankruptcy Code (2016), the banking system has been less tolerant of underperformers.

While banks are punching above their weight to recover dues, they must improve their own underwriting and credit risk management to ensure that loans don’t flow that easily to dubious prospects. At the same time, the firms currently in the ICU ward will be faced with hard choices between funding their debt traps or calling it a day. It’s much more complex than it seems but one thing is clear. The candle cannot infinitely burn from both ends.