Customer retention is dead. Long live customer agency

Point-of-sale financing vs customer retention

The right relationship is everything

We understand your world

We invest in your dreams…

When it comes to branding, banks have historically stuck to slogans that exude a warm and fuzzy feeling. Here’s why –

The evolution of the banking ecosystem can also be read as a history of tackling information asymmetry in financial services. Because a better grasp of the borrower’s financial information results in well-informed underwriting and, ultimately, mitigated exposure to risk.

Diamond, Greenbaum, Thakor and Boot summed it up like this –

Banks’ raison d’être resides in mitigation of information asymmetry between investors and borrowers.

The saccharine slogans resulted from a need to reduce this information asymmetry by developing deep relationships with the customers. Let’s back up a little and see how in many ways, it is these social relationships that laid the foundation of banking as we know it today.

An order of Fransiscan friars in Italy developed the montes pietatis in the 14th century, an early example of institutions that gave the needy access to capital.

Subsequently, the Industrial Revolution made access to banking commonplace for all in society, and these local bankers had a deep knowledge of their customers.

As the system grew, it assimilated more and more hierarchies. For instance, in 19th century UK, family banks merged into joint stock companies, launching the humble local banker into the status of a ‘branch manager’.

The customer base also expanded to include salaried workers, which made it difficult for the erstwhile banker to maintain personal relationships with each customer. The newly minted branch manager also no longer enjoyed the power he had to make decisions as a local banker.

This fact, exacerbated by the banking failures of the 1930s in the industrialised world, meant that the image of banking institutions began to take a hit. The social and economic impact of these failures, as well as World War II, gave banks the much needed impetus for change.

As a result, relationship-building became more systematised in banks.

Although it is usually associated with high-net worth individuals, the basic tenets of relationship banking apply to all demographics of customers – its foundation is the ability to up-sell and cross-sell financial products to existing customers.

With the advent of customer care in the 1960s, it became possible for banks, in spite of their elaborate and rigid hierarchies, to connect with individual customers and address individual needs. More importantly, the process of relationship building also gave banks insights into qualitative soft information about the customer – something absent from sources of hard data like credit bureau reports or transaction summaries.

This soft information is extremely exclusive, and proves useful in the long run as existing customers are retargeted for new products and services. Potentially, it could be used, on the bank’s discretion, in tandem with or to override decisions based on hard data and extend credit to a broader customer base, thereby diversifying the bank’s own loan books.

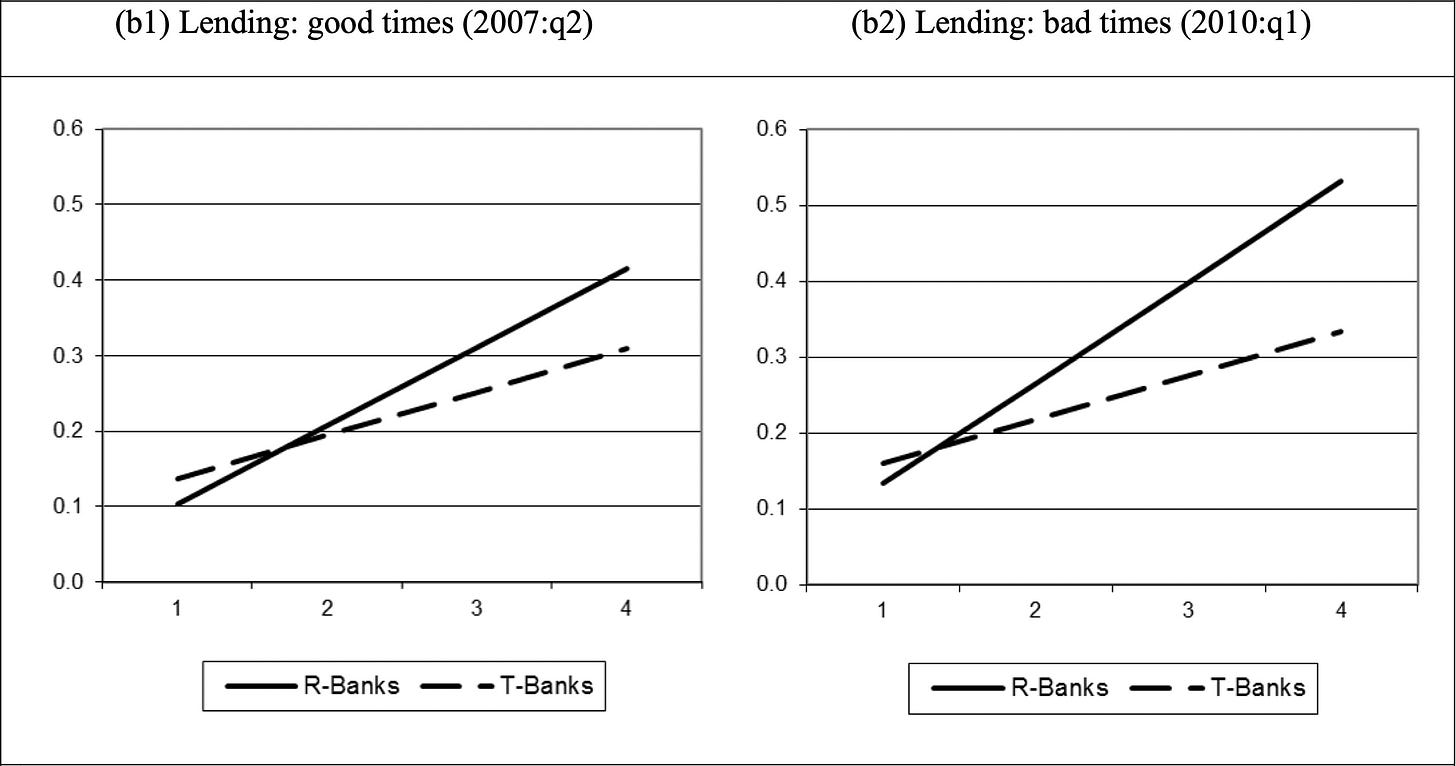

But this approach towards business is slow-burn, expensive and difficult to scale. However, it has been proven to pay off in times of crises. A paper published by the Bank of International Settlements showed that although relationship banks charged a higher intermediation spread in normal times to cover their operating expenses, they offered continuation-lending at more favourable terms than transaction banks to profitable firms in a crisis.

The shift to transaction-oriented banking

The concept of transaction-oriented banking is often seen as the opposite of relationship banking. It is driven by scale, commodification, and increased turnover at a small cost to the borrower.

The rise of non-physical credit delivery channels – first telephones, then netbanking and now smartphones – made it possible for lenders to package and deliver loans at a higher frequency to predetermined borrower personas at (more or less) standard interest rates.

But what made this possible?

The snowballing of invention in sourcing hard information.

Tech capabilities have facilitated the extraction of and access to absolute sources of truth like credit scores, bank statements, income, collateral, revenue, cash flows, etc. These can be quantified and used to build more or less accurate credit profiles. In fact, such quantification also supports collection efforts through the use of delinquency buckets.

If this was the invention of the aeroplane, the use of AI and ML in digital lending was like the invention of the rocketship just a few years later. Machine learning has enabled the creation of more precise credit risk models with the ability to scour billions of data points across “traditional” sources like the ones mentioned above.

More importantly, ML-based models can be used on alternative data (consensually sourced from customers) such as education, income history, spends not recorded in bank statements, etc. This has proven to improve credit access to ‘invisible primes’ – customers with low credit scores, but also low propensity for default by 70%.

The self-learning model quantifies this information to create alternative scores that can be used in addition to bureau scores.

The land of nothing matters

The quest to mitigate information asymmetry led banks from expensive and time-consuming soft information-gathering to hard information that facilitates scale in lending operations at a fraction of the cost. Although both strategies differed fundamentally, there were two key similarities:

Both approaches facilitate (to varying degrees) the extension of credit to low-credit score customers

Both approaches employed ‘push’ marketing to retain customers through cross- and up-selling.

Now, point-of-consumption financing solutions like embedded finance have become ubiquitous, thanks to open banking, bank-platform synergies, and the development of quantifiable data that arose from the need to know customers better. The question of information asymmetry is no longer as pressing as it once was.

Moreover, the question of access to consumer credit will also slowly lose importance as customers themselves choose to seek out financing at the point of sale itself – through an indirect and less aggressive ‘pull’ marketing of loan products.

What’s the future of customer retention?

One of the foremost criticisms of relationship banking is that it captures customers and does not allow them to explore possibly more beneficial products and services elsewhere. However, the unbundling of financial services and embedded finance will catalyse the fragmentation of customer retention and loyalty.

Examples of this are already visible – tech providers facilitate partnerships between platforms with multiple lenders, there is no dearth of lender aggregator platforms and digital lending apps, and customers are glad to abandon one service provider for another in search of a one-off reward.

Is that a bad thing?

That’s a question for moral philosophers. All I can say is that the death knell of the close-knit social relationships on which banking was built is loud enough for all to hear.

But, all is not lost. There are ways in which banks can still score over their competition and that’s by building solid products. This brings me to an upcoming discussion we’re hosting with experts from Yes Bank and Credit Saison among others on how UI/UX strategies can help build better credit products. Do reserve your spot and I will see you there!

That’s all from me this week!

Cheers,

Rajat